Problems of Presidentialism & the US Exception

by Fred W. Riggs, PhD (1917-2008)

by Fred W. Riggs, PhD (1917-2008)

This is a draft for the text published as “Conceptual Homogenization of a Heterogeneous Field: Presidentialism in Comparative Perspective,” in Mattei Dogan and Ali Kazancigil, eds. Comparing Nations: Concepts, Strategies, Substance. Blackwell, 1994. pp. 72-152.

ABSTRACT:

The American constitutional system based on the separation of powers was modeled on a transitional stage in the evolution of democracy as experienced in 18th century England. With Kings struggling to retain power against insurgent parliamentary forces, a precarious imbalance of power existed which the Founding Fathers copied in America, but sought to stabilize by an ingenious though precarious system of checks and balances. When other countries imitated this plan — as in virtually all of Latin America and some countries in Africa, Asia, and the post-Soviet arena — they typically experienced break-downs followed by despotism. By contrast, in the United States, despite severe crises such as a major Civil War and the Depression, the system has survived until today, a truly exceptional experience that calls for explanations, as proposed here.

Meanwhile, all the other industrial democracies, on the basis of 19th century developments in the UK, have adopted a significantly different constitutional design based on an the accountability of Cabinet Government to Parliamentary controls that evolved in England half a century after the American Revolution. Although no constitutional plan can guarantee success for any country, the likelihood that parliamentary regimes will survive is far greater than the prospects for those based on the separation-of-powers. Even the best recipe can be spoiled by a bad cook, but all cooks are more likely to succeed following better rather than worse recipes.

Note by the CoRRECT™ Webmaster:

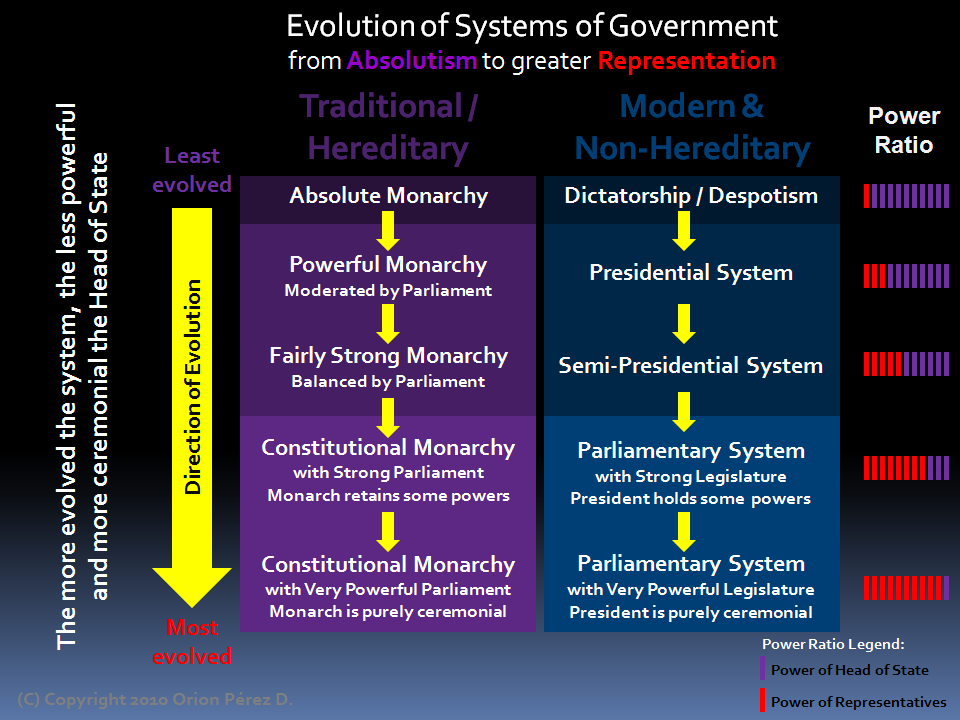

The “transitional stage” in the evolution of Democracy as mentioned by the late Dr. Riggs was also mentioned in the article “Senator Pangilinan & the Parliamentary System” where a diagram was presented describing the evolution of democratic systems from the original Absolute Monarchy in Feudal England all the way down to the Post-Victorian Parliamentary System (often within the framework of a ceremonial Constitutional Monarchy) that exists in today’s modern United Kingdom and several post-19th century former British colonies such as Canada, Australia, NZ, Bahamas, Barbados, Malaysia, Singapore, and others.

The diagram is shown below:

What we refer to as the US-derived Presidential System actually coincides with the system of a Powerful Semi-Absolute Monarchy which is merely one iteration away from an Absolute Monarchy. Most Presidential Systems are realistically just one step away from being Dictatorships. Parliamentary Systems are the most evolved systems.

CONTENTS

The Institutional Framework

Regime Authentification

THE TROUBLES OF PRESIDENTIALISM

The Presidential Establishment

The Legislative-Executive Chasm

The Party System

Bureaucratic Dilemmas

THE SURVIVAL OF PRESIDENTIALISM IN AMERICA

A Procedure

The American Presidency

The Legislative-Executive Balance

An Immense Congressional Agenda

A Centripetal Open Party System

American Bureaucracy

THE OUTLOOK FOR PRESIDENTIALISM

Comparing Presidentialist Regimes

NOTES

REFERENCES

INTRODUCTION.

The frequent collapse of presidentialist regimes in about 30 third world countries that have attempted to establish constitutions based on the principle of “separation of powers” suggests that this political formula is seriously flawed. By comparison, only some 13 of over 40 third world regimes (3l%) established on parliamentary principles had experienced breakdowns by coup d’etat or revolution as of 1985 (Riggs 1993a) (1)..

This empirical data substantiates Juan Linz’s argument that parliamentarism “is more conducive to stable democracy…” than presidentialism (Linz 1990, 53). While Linz admits that a presidentialist regime may be stable, as the American case shows, he does not try to explain this exception. Here I shall speculate about some of the practices found in the United States which seem to have helped perpetuate an inherently fragile scheme of government. These speculations need to be tested by systematic comparisons with the experience of the presidentialist regimes that have broken down. Pending such analysis, however, I will offer some impressionistic evidence to support the hypotheses presented below.

The discussion that follows is divided into three parts. –

- First: the institutional features found by definition in all presidentialist regimes;

- Second some critical problems inherent in any constitution based on “presidentialist” principles

- Third: American practices or traditions–frequently “undemocratic” in character–whose absence has apparently contributed to the collapse of presidentialism elsewhere.

* * *

* * *

PRESIDENTIALISM: WHAT IS IT?

Traditional institutional analysis antedated World War II and, unavoidably, focused attention on the well established polities of North America and Europe. Because all the stable industrial democracies (except the U.S.) adopted parliamentary forms of government and the other presidentialist systems were so unstable, however, the comparative analysis of presidentialism languished. Generalizations were based on a universe that included only one “viable” presidentialist regime and a good many parliamentary systems. Perhaps unavoidably, in this context, comparativists often assumed that the unique properties of governance in the U.S. could be attributed to environmental factors (i.e., geography, history, culture, economy, social structure, etc.) rather than its institutional design.

After World War II, Comparative Government experienced a radical re-evaluation of its fundamental premises in the light of the entry into the world system of over 100 new -third world- states. Many of them adopted constitutions that were quickly repudiated when military groups seized power in a coup d’etat, and it became apparent that formally instituted structures of government, typically based on Western models, did not or could not work as they were expected to. New approaches to comparative politics stressed functionalism or socio-economic determinism, and emphasized the crucial importance of external forces generated by the world capitalist system and international “dependency.” Political anthropologists emphasized the continuing vitality of traditional cultures and the comparative study of institutions languished. –

* * *

The Institutional Framework

In this context, formal institutions of governance were down- played as having secondary, if not trivial, importance. The fact that virtually all presidentialist regimes except that of the United States experienced authoritarianism and military coups was attributed to cultural, environmental or ecological forces rather than any inherent problems in this constitutional formula. Comparative presidentialism was neglected because it was considered useless to take “unsuccessful” cases seriously: how could failures teach us anything about the workings of a political system?

Moreover, since there was only one “successful” case, it could scarcely prove anything about the requisites for success in a presidentialist regime. It never occurred to anyone to think that the failures of presidentialism outside the U.S. were due to deep structural problems with the institutional design rather than with ecological pressures caused by the world system, poverty, Hispanic culture, religion, geographic constraints, demographic forces, etc. Nor did anyone imagine that constitutional failures could be used to test hypotheses about why American presidentialism had survived, or to learn more about the risks involved in this kind of system.

A counter-intuitive hypothesis might explain why presidentialism in the third world has been so unsuccessful. The newer presidentialist regimes may have rejected, as -undemocratic,- some practices that, perhaps unintentionally, have helped American presidentialism to survive. If so, these regimes were unconsciously caught in a double bind: to be more -democratic- involved taking risks that could lead to dictatorship, whereas to perpetuate representative government meant accepting some patently undemocratic rules. Unfortunately, I believe, our ignorance of the regime-maintaining requisites of presidentialism blinds us to the negative impact of progressive reforms on the survival of this type of democracy.

In the U.S. itself, debates about proposed “reforms” fail to consider their likely impact on the viability of the constitutional system. An old example involves the use of “primaries” to select candidates for election to public office, a nominally “democratic” innovation that has weakened its political parties. The current debate about limiting the terms of legislators in order to enhance democratic values fails to consider how it might affect the capacity of Congress to maintain the precarious legislative/executive balance of power that is so crucial for the survival of presidentialism.

A recent critic of President George Bush’s proposal for a constitutional amendment to limit Congressional terms to 12 years points out that it would increase the number of legislative ‘lame ducks,’ reduce the incentives for ‘men [and women] of potential public excellence’ to compete for elective office, increase the dependence of neophyte legislators on their professional staff and on bureaucrats and lobbyists, and diminish the scope of effective electoral choice open to voters. The same author, who directs political and social studies at the conservative Hudson Institute, argues that other solutions can be found to overcome the unfair advantages — mainly financial — that incumbents have when seeking re-election, without incurring the grave defects of the limited term option. I agree with all of these arguments, but they do not consider how the proposed change would affect the vitality and viability of presidentialism in America (Blitz, 1990). My guess is that electoral primaries have already weakened our constitutional system, and term limits, if adopted, would also have a negative systemic effect — but these are points to be discussed below at greater length.

Meanwhile, without rejecting any of the important findings of functional, ecological and world systems analysis, I suggest that we should also view all institutions as fragile human creations vulnerable to erosion or collapse? In addition to asking how a constitution actually works and how democratic and effective it may be, we need to consider its viability: what are its prospects for survival in a dangerous and highly interdependent world?

As ‘comparative politics’ evolved since the Second World War, it focused on intra-regional comparisons — that is, within the ‘First,” “Second” and ‘Third” Worlds. Such a geographically and economically determined framework has impeded institutional modes of analysis that require a global approach, including a North-South perspective that compares the effects of fundamental (constitutional) designs regardless of their geographic location or economic status.

* * *

The Environmental Context.

An institutional framework does not preclude environmental considerations. Economic level, class conflict, ethnic heterogeneity, geographic inequalities in the distribution of resources and population densities, religious, linguistic and cultural variety and so on, are ll significant and affect the destiny of states, as do such external forces as imperialism, foreign interventions, wars, migrations, and trade. Every regime confronts such -environmental – problems, some much more acutely than others.

Since both environmental pressures and regime types vary significantly, we must eventually try to link the two kinds of considerations. However, the impact of institutional variables is much easier to isolate and compare. It is perhaps easier, also, to compare the capacity of similar regimes to handle tough environmental challenges. To reverse this approach poses an extremely complex problem: it is extraordinarily difficult to reach safe conclusions about how any environmental variable affects the survival of democracy. Moreover, if our goal involves helping presidentialist regimes cope with tough environmental challenges, it is much easier to propose legal or constitutional reforms that might help instead of trying to change the environment–e.g., by promoting economic or cultural transformations, religious movements, and the rest.

* * *

Regime Authentification

Comparison of political institutions should begin with basic regime types, the constitutional principles that determine how a government is organized. No doubt every government has unique features, but it is easy enough to classify them into a few broad categories. Ideally speaking, the new (non-Western) states ought to devise indigenous institutions well adapted to their own needs and circumstances. So far, however, to cope with the problems of the modern world, they have relied for the most part on a few options borrowed from abroad, based mainly on the experience of presidentialist and parliamentary governments–or single-party authoritarianisms.

When these regimes fail, they typically give way to a military dictatorship and personal rule based on the seizure of power by public officials (mainly military officers) carrying out a successful oup d’etat Here I shall confine my analysis to a single regime type, one that has been widely emulated with disastrous results in some 30 countries of the third world, i.e., “presidentialism.”

The word, presidentialism (for reasons to be explained below) is used here to designate a type of -representative- government based, in principle, on the -separation of powers- between executive and legislative institutions, i.e.,. the President and the Congress. The meaning of “representative government,” or of “democracy,” will not be discussed here, but it presupposes the existence of a viable assembly (Congress or Parliament) whose members are elected from competing candidates by the citizens of a state. The separation of powers is a complex goal that cannot sustain itself simply because of a constitutional prescription. Rather, it results from adherence to a fundamental rule, namely that the head of -government- must have a -fixed term of office,- i.e., not be subject to dismissal by a no confidence vote of Congress: this does not preclude the power of impeachment for criminal conduct. The presidentialist separation of powers is viewed as a -result- of a single rule–the fixed term of the President. My definition of presidentialism, therefore, specifies this rule as its cause, rather than the separation of powers that is its consequence. The definition, of course, presupposes the existence of a viable legislative assembly without which any head of government may easily become a dictator.

* * *

The Defining Criterion

The definition of presidentialism offered here involves a sharp distinction between two key roles found in representative governments: that of head of -state- and head of -government.- This distinction is basic because non-presidentialist systems often have elected “presidents” who are heads of state but not heads of government. In parliamentary systems the two roles are easily distinguishable: the head of government is a prime minister, while the head of state is either a constitutional monarch or an elected -president.- Such “presidents” usually also serve for a fixed term and cannot be discharged by a parliamentary vote of no confidence, but this does not make their regimes “presidentialist.” The term president is often used also for the head of state in single-party and even military authoritarian regimes, but they are not therefore “presidentialist.”

In presidentialist regimes the elected head of government always serves concurrently as head of state. However, we must avoid defining a presidentialist system as one in which the head of -state- (president) is elected to office, a criterion that includes many non-presidentialist systems. A regime is presidentialist only if the effective head of -government- (President) is elected for a fixed term: the mode of election may be direct or indirect. To be “effective,” a head of government cannot be dominated by a single ruling party or a military junta, and the “fixed term” rule precludes discharge by a legislative no-confidence vote. (2)..

To repeat, by presidentialism I mean only those -representative governments in which the head – -of government is elected for a fixed term of office-, i.e., he/she cannot be discharged by a no- confidence vote of Congress. Note that this definition is -onomantic- rather than -semantic-: I am not reporting what the word, presidentialist already means. Rather, I am explaining a fundamental political concept and proposing a term to name it. Of course, presidential can be used to name this kind of system, but since this word is also used for other regime types– notably parliamentary systems with an elected head of state–there is less risk of ambiguity if we use an unfamiliar word, like presidentialist for the specific concept intended here. (3)..

Admittedly, this usage is not yet established. Many writers will say presidential when they mean presidentialis However, generalizations about “presidential” regimes are often invalid because they lump together some non-presidentialist with presidentialist polities. In this essay it is always necessary to know whether one is talking about the specific properties of a presidentialist system–as defined here–or using a loose concept that can also include parliamentary systems. These are different institutional forms of democracy and they have radically different properties that we need to understand. (4)

Scales of Variation The distinction between presidentialism and parliamentarism should be viewed as logical -contraries,- not -contradictories.- They are ideal types at opposite ends of a scale: in other words, representative government is not necessarily either presidentialist or parliamentary. There are intermediate possibilities, “semi-presidential” and “semi- parliamentary” in character.

Consider, for example, the French Fifth Republic, that Maurice Duverger has characterized as semi-presidential (1980). Although the head of -state- (president) is indeed elected for a fixed term of office, the head of -government- (premier) must command a parliamentary majority. So long as the president’s party has such a majority, the president may choose a premier of his own party, thereby permitting him to rule as the de facto head of government. Otherwise, the head of government (premier) may come from an opposition party in order to gain parliamentary support, as happened between 1986 and 1988 when President Francois Mitterand had to name an opposition leader, Jacques Chirac, as premier (Suleiman 1989, 11-15). At such times, the president is not a President. Juan Linz refers to the Fifth Republic as a “hybrid” (1990, 52). Scott Mainwaring also identifies Chile (1891-1924) and Brazil (1961-1963) as semi- presidentialist, even though their constitutional rules differed from those of the French Fifth Republic (1989, 159). Luis E. Gonzalez uses the terms, semi and neo-parliamentary to characterize the changing Uruguayan constitutions. The 1934 and 1942 charters, for example, had neo-parliamentary features insofar as the President had the authority to dissolve the legislature, and the legislature could censure the ministers, compelling the President to resign– but these powers were never tested (Gonzalez 1989, 3-4). The 1967 Uruguayan constitution retained the President’s right to dissolve Congress and hold new elections after a minister had been censured, but he would not, then, be required to resign (Gillespie 1989, 12-13). Giovanni Sartori proposes a four-type scale running from pure “presidential” [i.e., presidentialist] to pure parliamentary regimes. (5) This typology presupposes the maintenance of representative government. We need, however, to consider a second dimension of variation that runs from truly representative government to open authoritarianism or personal rule. Presidentialist forms may be retained even though their essential functions are lost.

Quasi-presidentiaist refers to a degenerated presidentialist system. Sometimes, regimes that were originally presidentialist become modified in practice when the principle of separation of powers is breached even though it remains nominally in effect. This has usually occurred when Presidential powers were expanded at the expense of the legislature that became a pliant legitimizing body, ratifying without resistance the decisions of the President. Although such regimes are presidentialist de jure, de facto they are not. We might put President in quotation marks to signify a role that appears to follow presidentialist rules but, in fact, violates them. It is often said that a weak legislature combined with “Presidential” domination is endemic in Latin America–countries like Argentina, Chile, Costa Rica and Uruguay provide the exceptions. Quasi-presidentialism may mask the dominant position of a hegemonic political party but it occurs more often, I believe, because an autocratic “President” or a dominant family or clique gains control of the Presidential office. Sometimes, also, unseen military “bosses” determine key policies while the formal office-holders, including the “President,” become their “puppets.” One may argue that most Latin American regimes are only “quasi-presidential”.

Whereas quasi-presidentialism results when an authentic presidentialist regime disintegrates, -pseudo-presidentialism- arises when a presidentialist charter is promulgated as a facade to cover some form of authoritarianism. For example, a military dictator establishing personal rule (Jackson and Rosberg 1982, 10) may adopt the title of “president” and sponsor a charter that copies the presidentialist formula: its elected assembly is politically impotent and the outcome of its presidential elections is predetermined.

* * *

Constitutional Transformations.

When a presidentialist regime experiences serious crises, one might assume (or hope?) that its political leaders would recognize the need for fundamental reforms and adopt constitutional amendments or new constitutions that move in the parliamentary direction. Instead, what usually happens is a regime breakdown that moves toward authoritarianism, whether formalistically through quasi-presidentialism or more overtly, after a coup d’etat, into pseudo-presidentialism.

Authoritarianism, whether in the form of quasi- or pseudo-presidentialism, is no more stable than pure presidentialism. Ultimately, all forms of dictatorship (including single-party and military authoritarianism) may be overthrown and replaced by constitutional regimes and representative government. Whenever this happens, serious attention is usually given to the design of a new constitution that might overcome the liabilities of earlier schemes.

In such episodes of re-democratization, parliamentary or semi-parliamentary options are often seriously debated, as happened recently in Brazil, Argentina, and Chile. However, it seems to be true that almost all ex-presidentialist regimes opt again for a new form of presidentialism. Under these circumstances, it is truly important to understand the survival problems inherent in the presidentialist formula. The practices that have enabled presidentialism to last in the United States might, perhaps, be institutionalized in other countries. However, I believe that most reformers would consider these practices (not presidentialism as such) so essentially undemocratic that they would reject them. When they recognize the costs involved in perpetuating presidentialism, they may be more willing to embrace options that move in the direction of parliamentarism. Until then, they are more likely, unwittingly, to approve presidentialism in a form that also involves quite democratic practices that, unfortunately, undermine the viability of the regime.

Presidentialism, per se, may be neither more nor less “democratic” than parliamentarism, although the American “founding fathers” explicitly prescribed a “republican” formula that they thought would avoid the dangers of populist “democracy.” However, even if one were to grant, provisionally, that presidentialism creates a more open and democratic regime than parliamentarism, one would have to balance this argument against the claim that, if presidentialism is likely to collapse into authoritarianism, then we ought to embrace a less democratic option that has better prospects of survival. Please understand: I do not claim that presidentialism is less democratic than parliamentarism. I only argue that if presidentialism is to survive as a regime type, heavy costs must be born, and some of these costs involve accepting undesirable (undemocratic?) practices.

* * *

THE TROUBLES OF PRESIDENTIALISM

In order to maintain the constitutionally prescribed separation of powers based on the election of a head of government for a fixed term of office, several fundamental and typical problems have to be solved in every presidentialist regime. Even though some of them may be solved in a given polity, failure to handle others can lead to deterioration or breakdown. Each major presidentialist problem is a kind of handicap: by itself it may not cause a breakdown but it becomes part of a cumulative and mutually reinforcing set of ruinous forces.

An executive/legislative relationship based on the fixed term of office set for the head of government constitutes the core problem: it generates other difficulties, however, each of which might precipitate a breakdown. Thus the separation vs. fusion of powers issue is not the only critical issue. In addition, each institutional feature of presidentialism–including the Presidential role, the Congress, the political party and electoral system, and the bureaucracy, as they relate to each other–needs to be examined. Questions involving a powerful third branch, the judicial system, are also relevant, but space limitations prevent discussion of this complex subject here. Might it be true, for example, that even a strong Supreme Court could not rescue a presidentialist regime about to collapse, or that a weak judicial system would not undermine such a regime if it had found other ways to cope with its major intrinsic problems? Such doubts reinforce my decision to ignore this important question here, but some tentative thoughts on it can be found in Riggs (1988c, 255 & 269-272).

* * *

The Presidential Establishment

Although the presidentialist formula only requires, by definition, the election for a fixed term of office of the head of -government,- Presidents also always serve as the head of -state-. In addition, the President is typically also the commander-in- chief and sometimes heads a leading party (or coalition of parties). These overlapping roles create vast expectations . The power vested in the office eems overwhelming, and regime tabilit appears to be assured. Since presidentialist regimes are vulnerable to collapse, however, this is an illusion. No doubt, so long as the regime persists, the fixed term of a President’s office assures more continuity of leadership–despite possible cabinet reorganizations–than can be found in a multi-party parliamentary system vulnerable to frequent cabinet crises. In practice, nevertheless, Presidents are severely hampered in their leadership roles, and their inability to fulfill popular expectations often leads to crises and regime breakdowns. These limitations may be viewed from several perspectives.

* * *

Fusion of Roles.

As head of -government- every President has to make controversial policy decisions that unavoidably alienate substantial portions of the population. Even when a Government’s policies are widely supported, failures and injustices in their implementation are often blamed on the President. Yet Presidents, in their capacity as heads of -state,- are expected to symbolize and attract everyone’s loyalty, providing a common focus of patriotism for all citizens. Clearly, the requirements of the first role often clash with those of the second.

In parliamentary regimes, where loyalty to the head of state (“king” or “ceremonial president”) can easily be dissociated from support/opposition to the head of government (prime minister in cabinet), citizens can more easily sustain their patriotic loyalty to the State while opposing the policies of the Government. When the two roles are linked, however, citizens easily confuse their dissatisfaction with Government with disloyalty to the State. As a result, opposition to the current Administration may produce discontent with the Constitution and provide support for coups and revolutionary movements: opposition to Government easily becomes treason to the State; dissent becomes revolution. The absence of a separate head of state may also deprive the regime of an important moderating force to help conciliate opposing political movements or tendencies in times of emergency.

* * *

Fixed Term of Office.

The fixed term poses a double liability. In the case of effective Presidents it forces them out of office prematurely: one example may be that of Nobel prize winning President Oscar Arias Sanchez of Costa Rica–his four-year term expired in 1990 and he could not be reelected. The more usual cost, however, is that paid for an ineffectual President who, nevertheless, cannot be constitutionally discharged from office (except for criminal conduct as determined by impeachment). Ironically, one of the reasons for such ineffectiveness is precisely the fixed term: ambitious politicians, even in the President’s own party, often feel that they can best advance their own careers by distancing themselves from the President, building an independent (oppositional) base for future political campaigns, and establishing themselves as opponents of the current regime. This -lame duck- phenomenon occurs in the U.S. near the end of every President’s second term in office, but in many other countries we might even speak of a -dead duck- syndrome that afflicts new Presidents shortly after they assume office. In part this is due to constitutional barriers to any re-election of a President: in the American case, the possibility of at least one re- election (two or more until the enactment of Amendment 22 in 1951) enables a President to postpone the lame duck syndrome.

A dead duck President is not only gravely handicapped, but the growth of political opposition and popular discontent may well bolster the ambitions of a military cabal conspiring to seize power. A coup d’etat is the functional equivalent, under presidentialism, of a removal effort that, in parliamentary regimes, can be achieved by a no-confidence vote. Since coups involve suspending the constitution, Congress is also dissolved, whether or not its resistance contributed to the failures of the Presidency.

* * *

Veto Groups vs Opposition.

A President’s role as head of government is also severely limited by the pervasiveness of -veto groups- such as the legislature, the courts, and the bureaucracy, plus a fractionalized party system. Although these diverse bodies can block executive action, they cannot formulate the coherent alternatives that the political opposition can often produce in parliamentary regimes. Such an opposition may also compel Government to modify policies in a consociational direction (Lijphart 1989, 8), something that presidential veto groups normally fail to do. The possibility that an opposition can replace them means that cabinets must take their views seriously, whereas Presidents are tempted to view their opponents merely as hostile forces to be subdued.

Mainwaring tells us that in the Latin American presidentialist democracies, Presidents have often been able to initiate policies but unable to win support for their implementation (1989, 162). Thus veto groups can block action but they are powerless to bring alternative (opposition) parties to power. Since all Presidents, despite growing opposition and political impotence, must cling to office until they meet their scheduled deadlines, a kind of self-induced nemesis drives them into the dead end of their “lame duck” terms.

* * *

The “Winner-take-all” Syndrome.

In parliamentary systems, the election of a ceremonial president means relatively little, while the election of party members to Parliament means a great deal–especially to party supporters. Even small parties may “win” to the degree that some of their candidates become Members of Parliament and may even join the Government.

By contrast, in presidentialist systems the electoral stakes are much higher and more concentrated because so much hinges on the selection of a governing President–often, indeed, it is more of a personal than a partisan victory. Presidentialism, writes Juan Linz, “is ineluctably problematic because it operates according to the rule of ‘winner-take-all’–an arrangement that tends to make democratic politics a zero-sum game, with all the potential for conflict such games portend” (1990, 56). There are many losers under presidentialism. Not only defeated parties but even members of a winning party–especially rival candidates for nomination–may feel that they have lost everything when a President is elected, leading to great discontent, alienation and the “dead duck” syndrome, as noted above.

To the degree that patronage prevails–and it is pervasive in all presidentialist regimes–a host of public officials may feel that their continuation in office depends on victory for the ruling party, and private interests supported by the Government also have a large stake in its survival. Consequently, a Presidential victory is a triumph for supporters of the winning candidate and a great loss for opponents (Linz 1990, 56). Understandably, their frustrations easily translate into popular resistance to the Regime rather than loyal opposition to the Government.

In pathological cases, the stakes seem so high that Presidents resort to unconstitutional means to maintain their power, including corruption, violence, and sponsoring proteges (relatives and cronies) so as to perpetuate a “family” dynasty, or even to compel constitutional changes that permit their own reelection. Corruption and violence at the polls often occur as a likely consequence of the high stakes winner-take-all contest.

Such contentiousness may be amplified by the electoral rules. In Peru, for example, until 1979, a President could be elected by a one-third plurality, and Congress could name the President when no candidate won a third of the votes. In Peru’s 1962 election, the leftist (APRA) party’s leader, Haya de la Torre, “beat Balaunde [of the centrist Accion Popular party] by less than one percentage point, 32.9% to 32.l%, with Odria third at 28%.” Since this threw the final choice to Congress, Haya sought first to make an alliance with Balaunde who rejected him, calling instead for new elections (APRA had been charged with electoral irregularities). Haya then turned to his arch rival, Odria, of the right wing PPC. “The specter of a government led by the presidential candidate who had finished third, in an ideologically disparate coalition between two parties that had been enemies for decades, may have been the last straw for the military. The coup came within two days” (McClintock 1989, 28-9). Thus the high-stakes winner-take-all game may even lead the losers to support the desperate expedient of a military coup.

* * *

A Fragile Political/Administrative Base.

The institutional foundations of a President’s rule are inherently fragile. We may analyze this problem separately at the political (partisan) and the administrative (bureaucratic) levels, although in fact the two are closely interlocked.

At the political level, the contrast with parliamentary systems is instructive. The dependence of cabinets on parliamentary support means both that party discipline is necessary and that a government without parliamentary support must resign. The resulting fusion of powers often enables parliamentary governments to act decisively. By contrast, no such interdependence occurs under the presidentialist separation of powers where a persistent stalemate can block executive action.

Ideally, perhaps, a President’s authority ought to rest on a party system that mobilizes voters to support candidates for election to public offices so that a winning party can ensure Congressional support for Presidential policies. In fact, however, this rarely occurs. Presidentialist party systems vary widely in their capacity to mobilize political support for a President. Some are highly disciplined and others extremely loose, two equally dysfunctional extremes. Disciplined parties, as found in Chile, have prevented the President from getting necessary

Congressional support whenever he lacked a majority. Alternatively, as in Brazil, where party members freely vote their personal preferences, Presidents have responded by flagrantly overriding or flouting the parties that had formally supported their candidacy (Mainwaring, 1990b, 21). Even in the United States, as at present, the majority party in Congress need not be the President’s party, setting the stage for persistent conflict and deadlocks.

In multi-party systems, the President is likely to win only a plurality of popular votes, even though a technical majority may be formed in second round run-off elections or Congressional voting. Such majorities are ad hoc coalitions that soon fall apart, denying the President genuine legislative support for his/her policies: according to Mainwaring, “The combination of presidentialism and a fractionalized multiparty system is especially unfavorable to democracy. (Mainwaring 1990b, 25). See also (Valenzuela 1989, 33).

Even when, in a two-party system, the President’s party has a Congressional majority, the fact that the President cannot be discharged by a majority vote of no confidence may mean that members of the President’s party have little to lose by not supporting a Government bill they do not like. Moreover, party factionalism can also mean that many members of the ruling party consistently vote against the chief executive’s policies and leadership. No doubt, when party discipline is strong, as it has been in Argentina, a Congressional majority will assure support for Presidential policies. Nevertheless, even though the separation of powers may serve its original purpose of preventing arbitrary government, it often fails to provide the political support Presidents require in order to govern effectively.

The inability of Presidents to implement policy is compounded at the administrative level, as illustrated pointedly by the precarious dynamics of “cabinet” formation. A President needs the help of a highly qualified top echelon of department heads and bureaucrats who can administer public policies effectively and also secure Congressional and legal support for Administration policies. However, Presidents jeopardize the separation of powers if they rely either on members of Congress or on career officials to head their departments and form a cabinet. Accordingly, they seek to enhance Congressional support by naming party activists from outside Congress, or they recruit personal followers (even relatives) from the private sector to fill these posts, and to staff the Presidential apparatus, by-passing both elected politicians and experienced public administrators. Consequently, a highly personal style, inter-departmental conflicts and lack of institutionalization at the top levels of Presidential administration typically hampers the processes of governance in presidentialist regimes.

* * *

The Legislative/Executive Chasm.

Consider the case of Ecuador, which has experienced frequent regime breakdowns, but has restored democratic procedures since 1979. Nevertheless, acute tensions between President and Congress persist, according to Catherine Conaghan, who tells us that shortly after the elections of 1984, “Congressional activity came to a stand still after sessions were marred by tear-gas bombings, fisticuffs on the floor of the assembly, and walk-outs by legislators on both sides. Meanwhile, [President] Febres Cordero had decided to physically bar the new appointees [named by Congress to the Supreme Court] from using their offices and banned the publication of the appointments…” (Conaghan 1989, 20). In 1987, the President was kidnaped by Air Force paratroopers who released him only after he had agreed to confirm the amnesty granted by Congress to two leading opponents of the administration (23-4).

“From 1979 through 1988, Ecuador staggered through a succession of executive-legislative confrontations that created a near permanent crisis atmosphere in the polity” (Conaghan 1989, 25). “Even when Presidents enjoyed a pro-government majority in Congress, the majority could easily erode under the pressures of interest groups and electoral calculations. Congressional opposition was a standard feature in the interruption of Presidential terms with interest groups and the armed forces joining in the fray” (Ibid., 8).

When a President is “…incapable of pursuing a coherent course of action because of congressional opposition… in many cases, a coup appears to be the only means of getting rid of an incompetent or unpopular president..” (Mainwaring 1989, 165). A similar argument can be found in Linz (1990, 53). Stalemate is even more unavoidable when–as noted above–the President’s party has only a minority in the Congress.

To overcome such impasses, Presidents frequently strive to dominate the assembly, a tendency that, in effect, vitiates the principle of separation of powers, leading to quasi-presidentialism and the erosion (or destruction) of presidentialist legitimacy. Embattled Presidents are often tempted to resort to desperate and even unconstitutional measures in order to bypass Congress and achieve their goals (Mainwaring 1989, 168-9). Sometimes, as in the Philippines in 1972, the President suspends Congress and rules by martial law and executive orders.

More often, as in Brazil, according to Mainwaring, all its democratic Presidents sought “…to bypass Congress by implementing policy through executive agencies and decree-laws… the practice of creating new agencies and circumventing congress for major programs…” has grave costs (1990b, 15). “When Quadros and Goulart were frustrated with Congress…they appealed to popular mobilization–with disastrous results in both cases… This strategy was catastrophic, as it further alienated major institutional actors, including the armed forces…” (1990b, 16).

Military interventions are not often explicitly due to an overt impasse between the President and Congress, but rather are attributed to habitual executive abuse or misuse of power provoked by a long-festering history of such conflict. The absence of a coherent opposition that could replace the Government–as noted above–often tempts a President to persist in unwise projects that undermine popular support. No cabinet officer or legislator is powerful enough to compel the President to make serious policy revisions. The frequent replacement of cabinet members not only reflects Presidential weakness but, reciprocally, generates sycophantism and intimidates those who might be able to correct a misguided President.

Since impeachment cannot replace the Government by an opposition party, even fierce opponents may oppose a procedure that will merely replace the President with an even more objectionable vice president. Consequently, the fixed electoral cycle of presidentialism creates structural rigidities that are readily overcome in the alternative parliamentary model by the threat of a cabinet crisis and/or new elections whenever the current leadership is seriously discredited. Is it, therefore, surprising that in such an environment a cabal of officials, mainly military officers, should seize power and overthrow the presidentialist regime?

* * *

Congressional Problematique.

Since the presidentialist formula requires that members of Congress as well as the President be elected for a fixed term of office, it is apparent that every effective Congress will have to cope with a vast and inherently unmanageable agenda. By contrast, in any Parliament, members mainly need only to agree or disagree with Government policies. Even members of a Government party who disagree with its policies will usually support them in order to avoid the likelihood of a new election in which they might lose their seats.

In all contemporary polities the number of complex issues calling for attention is so vast and controversial that it is really impossible for any body of legislators to study and reach collective agreements on all of them. The danger, then, is that an overloaded Congress will fail to act or find itself deadlocked in major controversies. If it is too compliant with Presidential policy demands, it becomes a mere rubber stamp, or it may simply refuse to consider many of the issues that might have been placed on its agenda. If, however, it habitually rejects Government proposals, or offers alternatives that the President will only veto, it can bring the processes of governance to a halt.

Moreover, members of Congress face competing demands that must be terribly frustrating. They are pressured by clients seeking patronage appointments, by local constituencies seeking funds for “pork barrel” projects, and they must mobilize support for re-election campaigns. Essentially, every Congress is placed in a kind of “no-win” situation from which it vainly struggles to extricate itself. Ultimately, it must share with the President a heavy burden of criticism that, all too often, generates military intervention and the breakdown of the regime.

* * *

The Party System

Since a presidentialist regime is, by definition, a form of representative government, it needs to have an open party system: i.e., it needs electoral competition between two or more effective parties. I believe this is true because the maintenance of genuine legislative power is impossible whenever one party regularly dominates the elected assembly. A one-party system (as in Communist regimes) leads to complete party control of the elected assembly. Even a hegemonic party, in a polity that permits genuine opposition parties, nearly suffocates the Congress. Mexico provides a classic case. There, all the advantages resulting from electoral success belong repeatedly to the PRI and the Congress becomes a pliant legitimizing instrument. The separation of powers required, by definition, in a presidentialist regime is, therefore, incompatible with hegemonic or one-party rule–what I shall refer to as a closed party system. By definition, opposition parties may be permitted to run candidates in free elections, but if they have no real chance of winning power, then the party system is really “closed.”

An open party system, by contrast, is one in which two or more parties have real possibilities of winning power. We cannot use multi-party for this concept because a two-party system is also “open.” No doubt the distinction between two and multi-party systems is significant–as is the distinction between single and hegemonic party systems. However, I see them as sub-types of a more fundamental distinction, i.e., between open and closed party systems. Moreover, among open party systems there is a more fundamental difference based on the dynamics of inter-party competition that we need to consider here.

* * *

Dynamics of Centrifugalism.

Among open party systems, the most fundamental distinction, I believe, involves the degree to which power is centrifugalized (polarizing) or centripetalized (centering). In the context of this distinction, we can better understand the two- party/multi-party contrast. (6) I believe that the survival of presidentialism is promoted by an open centripetal party system and undermined by one that is centrifugal or closed.

Centripetal forces arise when different parties compete mainly for center votes, i.e., the support of regular, mainstream voters who think of themselves as “independents,” willing to support candidates of any party or even to split their tickets, as current interests, policy issues or political personalities suggest. By contrast, centrifugal forces prevail when more extreme positions are taken by parties seeking to attract the support of non-voters. This typically involves proposing dramatic, populist, costly and controversial policies likely to win the support of apathetic or alienated citizens who normally cannot or will not vote. Unfortunately, most presidentialist regimes have developed centrifugal party systems, thereby creating self- destructive spirals based on circular causation.

* * *

Multiparty Systems.

A voting system that rewards small parties offers strong incentives for marginal groups to become organized and present extremist platforms that can mobilize special interest groups of many kinds, be they street sleepers, religious sects, or ethnic communities or social classes. Such pressures produce multi-party systems that undoubtedly create grave problems for parliamentary systems but they need not destroy them. No doubt each party represented in a coalition cabinet can exercise a veto power by threatening to withdraw, but it also needs the support of other coalition members to achieve any of its goals, often leading even extremists to support consociational accommodations.

By contrast, a centrifugal multi-party system surely undermines any presidentialist regime because its polarized parties lack pressure points vis a vis a fixed-term head of government. Although presidential candidates may temporarily seek the support of extremist parties, as when forming pre-election coalitions, the withdrawal of partisan support will have little influence on Presidents in office. Small parties lack bargaining power and Presidents have no built-in structures to counteract the polarizing tendencies of a centrifugal party system. Indeed, any President who seeks to meet the demands of extremists in Congress soon antagonizes the main-line parties and loses the support needed for policies of more general interest.

Multi-party systems usually lead to minority governments, in two senses. First, a plurality government is one in which a President has won office with a plurality vote, but no absolute majority of the popular vote and, second, a divided government is one where the President continuously faces an antagonistic majority in Congress (where the same party prevails in both branches we may speak of party government). Minority government in both senses is almost unavoidable because of the centrifugal dynamics inherent in multi-party systems : plurality Presidents lack the popular mandate needed to lead effectively, and minority governments cannot gain Congressional support for their policies.

In most of Latin America, sad to say, multi-party systems prevail. Among them, the most successful was probably Chile, “… the only case in the world of a multiparty presidential[ist] democracy that endured for 25 or more consecutive years” (Mainwaring 1989, 168). In Chile, Congress was called upon to make the final choice of a President but, in this situation, a temporary coalition of highly disciplined parties, formed to support the winning candidate, usually soon fell apart (Valenzuela 1989, 32). Thus, “…there was an inadequate fit between the country’s highly polarized and competitive party system, which was incapable of generating majorities, and a presidential[ist] system of centralized authority… As minority Presidents…Chilean chief executives enjoyed weak legislative support or outright congressional opposition. And since they could not seek reelection, there was little incentive for parties, including the President’s own, to support him beyond mid-term” (Valenzuela 1988, 33-4). The resulting sense of “permanent crisis” culminated in 1974 in the Pinochet coup and dictatorship.

A different kind of multi-party presidentialism is found in Brazil where “…Presidents could not even count on the support of their own parties, much less that of the other parties that had helped elect them. Brazilian parties in the two democratic periods have been notoriously undisciplined and incapable of providing consistent block support for presidents” (Mainwaring 1990b, 5). They have tried to cope with the deadlock of congressional opposition based on an extremely fragmented and fluid party system by developing an “anti-party discourse” and have “engaged in anti-party actions.” Often they were “recruited from outside or above party channels…” They usually avoided strong links with any party in order to enhance their political appeal to a broad range of public opinion (Mainwaring 1990b, 9-10).

Whether the individual parties are disciplined or not is certainly important, but I believe that a more important consideration is the centrifugal dynamism of all multi-party systems. Although these dynamics may even invigorate parliamentary systems, they ultimately destroy presidentialist regimes, producing both plurality and divided governments.

* * *

Two-Party Systems.

It is widely thought that two-party systems are generated by presidentialism and conducive to their survival. Actually, multi-partyism is more common in presidentialist regimes, and two-partyism by no means assures their survival. According to Mainwaring, “Two party systems are the exception rather than the rule in Latin America, but among the regions’s more enduring democracies, they are the rule rather than the exception”– including Colombia, Costa Rica, Uruguay and Venezuela (Mainwaring 1990b, 25).

However, a two-party system is not necessarily a permanent feature of any presidentialist regime, and by no means assures its survival. Since the 1984 election, Uruguay may no longer be classed as a “two-party system” and Venezuela has been a two-party system only during the last 20 years or so. In Asia, two-partyism prevailed in the Philippines from 1946 to 1972, after which President Ferdinand Marcos imposed martial law, suspended Congress, and created his closed system dominated by the New Society Movement (KBL) (De Guzman and Reforma 1988, 87-95). Actually, it is very difficult to maintain a viable two-party system: it may evolve into a multi-party or hegemonic party system.

Ideally, a two-party system will enable Presidents to secure a majority vote and a popular mandate to rule, with the support of a party majority in Congress. This premise is based on the familiar parliamentary model and fails to appreciate the basic fact that, because of the fixed term, presidentialist regimes lack the basic motor of parliamentarism that promotes party discipline. Even when the President’s party has a Congressional majority, there is no way to guarantee support for the President’s program.

To understand the acknowledged linkage between two-partyism and presidentialism we must first recognize that a two-party system may be centrifugal or centripetal: overcoming executive/ legislative conflicts is much easier with a centripetal two-party system than it is when that system is centrifugalized. To visualize the dynamics of a centrifugal two-party system, consider the situation in Uruguay, often mentioned as a leading example of successful two-party democracy. There, the Colorado party actually held power from 1865-1973–except for a brief interim (1958-62) of control by the opposition Blanco party–suggesting a de facto hegemonic party situation. A military group seized power in 1973, and democracy was not restored until 1985.

Centrifugalization in this “two-party system” was driven by party factionalization and high voter turnouts, leading to deep cleavages between the President and Congress (Gillespie 1989, 15; Gonzalez 1989, 14). The main explanation can be found in Uruguay’s exceptional scheme of proportional representation that permits party factions to present separate lists. This system, known as the “Double Simultaneous Vote,” has produced highly contentious intra-party factions (Gillespie 1989, 15). Even though each list goes under the label of a major party, the candidates on each faction’s list compete with each other just as they would in a multi-party system, and they also provoke wide-spread electoral participation. Consequently, Presidents typically face strong resistance within their own party–in addition to the opposition party.

Thus, when Oscar Diego Gestido was elected in 1967, his faction controlled only a fraction of the Colorado deputies. The resulting standoff, complicated by some quasi-parliamentary features of the constitution, resulted in no “…real control over the Executive but a permanent hindrance of its functioning which ironically increases the tendency toward coups.” In 1973 a military group seized power and dissolved Congress, although Juan Maria Bordaberry was allowed to remain as nominal “President” (Gillespie 1989, 15-17; Gonzalez 1989, 7-8).

A similar rule permits party factions to run separate electoral lists in Colombia and helps to explain the complexity of this country’s highly factionalized and centrifugal “two-party” system. “Factionalization forced each President to create and recreate an effective governing coalition within Congress, making the National Front period resemble a multi-party system” (Hartlyn 1989, 16). Although leading factions of the two main parties supported the Government, other factions of each party went into opposition. Immobilism and deadlock resulted. For further details see Hartlyn (1989, 15-20).

Since multi-party systems are necessarily centrifugal, only a two-party system is compatible, in the long run, with presidentialism. However, this is possible only if the system is centripetal, and as Uruguay and Colombia demonstrate, two-party systems may be highly centrifugal. We will clarify the problem, therefore, if we say that a centripetal open party system is needed. If, as I have argued, multi-party systems are necessarily centrifugal, this means that it must be a two-party system, but having only two parties is not sufficient.

* * *

Electoral Foundations.

When our focus is on the centripetal/centrifugal distinction among open party systems, we can easily see that the electoral system provides the most important explanation. In general, a wide variety of multi-member-district proportional representation– i.e., PR–systems produce centrifugalized party configurations (normally, but not always, with more than two parties). The attempt to secure a popular majority for the President by means of a second-round run-off election cannot nullify the effects of PR in the first round. Moreover, when congressional elections coincide with the first round balloting for President, as may often be the case, it becomes most “unlikely that a President will enjoy a clear-cut majority in Congress.” This proved to be the case in Ecuador where many parties have proliferated (Conaghan 1989, 12-3).

The rhetoric of two- and multi-party systems lulls us into our preoccupation with the number of parties in a polity and distracts attention from an equally necessary factor, i.e., the internal distribution of power in a party. I believe the survival of presidentialism is as much affected by party-structure as it is by party-system. Yet we cannot easily discuss this dimension because our vocabulary is inadequate. We tend to make a simplified dichotomy between “disciplined” par ties, such as we normally find in parliamentary systems, and the “catch-all” parties found in the United States and, for example, in Brazil. We may also assume that PR leads to disciplined parties and SMD voting to loose parties–generalizing from U.S./European comparisons.

The comparative study of presidentialist regimes will show us, however, that such notions conceal a far more complicated reality in which, assuredly, electoral systems play a role, in combination with regime type. I believe we need to distinguish between at least three dimensions of power distribution found in all political parties: geographic, functional, and relational. We can use centralized/localized to talk about the geographic dimension; concentrated/dispersed for the functional dimension; and integrated/isolated to discuss relations between political parties and other social organizations based on religion, ethnicity, class, occupation, etc. Here I shall focus on the first two, leaving the third for later comment.

I shall use centered to characterize a political party where power is both centralized and concentrated; and fluid for a pattern in which power is both localized and dispersed. Discipline is properly used for the willingness of all legislators belonging to a given party to vote as instructed by their leaders. Clearly the more centered a party, the greater the likelihood that its parliamentary members will be disciplined. By contrast, members of a fluid party are likely to be undisciplined, often refusing to follow their party’s line. We need to retain this distinction between the internal power structure of a party and the voting behavior of its members in an elected assembly.

A party in which power is both centralized and dispersed is factionalized, as illustrated by the Uruguayan and Colombian parties. This pattern is produced, I believe, by an unusual form of PR (the “double simultaneous vote”) that produces a centrifugalized two-party system. Legislative voting will be disciplined (within the factions) and undisciplined (in an all-party sense). A neologism may be required to talk clearly about such cases: we might speak of dia- discipline in the case of factionalized parties.

Party power may be both localized and concentrated in the form of urban machines, such as Tammany Hall and many other political clubs typical of an earlier period in U.S. history. Rather awkwardly, we might speak of such a party as machined or machinist, but I use these words here only to illustrate our need for better terms. Legislative voting in such parties might also be dia-disciplined, but with members following orders from local machine bosses rather than from national faction leaders.

More importantly, however, we need to see that normally PR in a presidentialist regime produces a multi-party system in which the power distribution in individual parties can vary between centered and fluid. Fluid parties are found in Brazil, producing a chaotic Congressional arena where Presidents have to bargain with many individualistic members in order to secure clientelistic support for their policies, often by means of patronage and local (pork barrel) projects. “The extremely loose nature of Brazilian parties has added to the problems caused by the permanent minority situation of Presidents’ parties. Presidents could not even count on the support of their own parties, much less that of the other parties that had helped elect them” (Mainwaring 1990b, 5).

Similarly, in Ecuador, “…politicians of every stripe appear to be afflicted with a significant amount of distaste and disdain for the party system in which they operate.” “Rather than using presidential resources to build up his own party, Febres Cordero [as other Presidents had done] preferred to by-pass parties altogether and create a clientelist network…” (Conaghan 1989, 30) Thus, the efforts of Presidents and other politicians to undermine party solidarity often stimulates, by circular causation, the disruptive effects of fluid parties on legislative performance and the growing frustrations of the chief executive. Conaghan remarks that “What is striking in Ecuadorean political culture and style is the extent to which it has been permeated by an anti-party mentality…” (29). Alternatively, as I propose, one might see the extreme fluidity (localization and dispersal) of such parties as a normal feature of presidentialist regimes that use PR electoral systems.

It is equally normal, however, for such systems to produce highly centered parties, and they are equally dysfunctional for the maintenance of presidentialist regimes. The best example can be found in Chile where well disciplined (ideological) parties often combine to produce a solid opposition front whenever a President cannot sustain the majority coalition in Congress that brought him to power (Valenzuela 1989, 32-3).

In parliamentary systems, of course, PR also leads to centered parties–the dynamics of parliamentarism simply renders a fluid party non-viable. Moreover, centered parties are functional for the maintenance of parliamentary accountability because they produce discipline. Of course, reciprocally, the need for discipline has a feed-back effect which encourages electoral rules that generate centered parties. In presidentialist systems, by contrast, PR can produce parties that are fluid, centered, or factionalized: always in a centrifugalized party system and always dysfunctional for the maintenance of presidentialism. Moreover, neither President nor Congress seems to have any systemic means to counteract these party dynamisms.

Fortunately, between the polar extremes identified above some intermediate intra-party power distributions are also possible. Here our vocabulary is, again, quite inadequate. Provisionally, I shall use responsive to characterize an intra-party distribution of power that combines local autonomy with headquarters guidance, and permits intra-party groups to organize informally but not to become oppressively prominent. On the two basic power dimensions, responsiveness falls between centered and localized, and between concentrated and dispersed. In the section, Predictable Enigma, I argue that the survival of presidentialism in the United States hinges, among various factors, on the responsiveness of its political parties and the semi-disciplined voting patterns that this engenders. The causes are no doubt complex, but they surely include reliance on a single-member-district (SMD) plurality system for the election of legislators, plus the freedom to abstain from voting and a variety of other factors that will be explained below, under Centripetal Party System.

[figure 1 may be inserted here]

* * *

Bureaucratic Dilemmas

The urgent need of any chief executive to be surrounded by competent and loyal officials capable of managing and coordinating the administration of government directs attention to a major problem that is easily overlooked by analysts predisposed to focus on the “political” aspects of governance at the expense of its “administrative” dimensions. Yet failure to administer well has dire political consequences. Public confidence declines and discontents soar, producing the kinds of unrest that lead, so often, to revolutionary movements and coups.

Moreover, many activities that are nominally administrative in character actually have strong political implications–for example, appointments to public office and administrative reorganizations, including the establishment of new agencies, can vitally affect a President’s power position, and influence the disposition of members of Congress to support or oppose a President’s policies. Perhaps, above all, bureaucratic power often expands to such a degree that public (especially military) officials become major actors in the political arena–sometimes even seizing power by a coup d’etat. Because the political implications of bureaucratic dilemmas are so often misunderstood, we need to take a closer look at these problems as they occur in presidentialist regimes.

* * *

The Power of Modern Bureaucracy.

The main instrument for administering any modern government is typically a bureaucracy whose members–military as well as civil–depend largely on their salaries to support themselves and their dependents. This feature of modern bureaucracy contrasts with the situation found in traditional bureaucracies where modest official stipends were normally supplemented by various kinds of legal but non-official income (Riggs 1991, 2-6). (7)

The significance of this fact becomes apparent when we remind ourselves that officials, like all other people, have their own interests to defend. However, their control over public offices and resources gives them weapons of power (especially in the armed forces) not available to most citizens. Unless their incomes are secure and their conduct is well monitored, guided and supervised by constitutional organs and popular forces, bureaucrats are easily able to exploit public office for personal advantage, as by widespread corruption and sinecurism. When they really feel threatened, they can also, under military leadership, seize power by a coup d’etat.(8)

The Need for Patronage. The public interest in contemporary societies requires that many bureaucrats, especially those in leadership and technocratic positions, be experienced and highly qualified to perform difficult tasks. The necessary qualifications are best assured by the establishment of a “merit” system designed to recruit well trained persons whose continuing (tenured) experience in government service enables them to perform effectively.

In parliamentary democracies–and even under single-party domination and in traditional monarchies–the development of experienced cadres of public officials is usually possible, and ruling elites or cabinets are able to rely, for the most part, on career bureaucrats to staff and implement their politically-driven policies in ways that are essentially technocratic and professional.

By contrast, in presidentialist regimes, the structurally precarious position of Presidents–for reasons discussed above–would be seriously jeopardized were they to depend on career officials to staff the highest bureaucratic offices, including cabinet positions. Moreover, Presidents cannot recruit sitting members of Congress to serve as cabinet members without endangering the autonomy and power of the executive office, nor is it possible for non-elective cabinet members to hold seats in the assembly without jeopardizing the balance of power. In this necessarily precarious position, Presidents have no option but to recruit a large number of leading officials, starting at the cabinet level, from outside the government service: they cannot be either career officials or elected politicians.

Consequently, heavy reliance on patronage appointments (clientelism, cronyism and spoils) is a prevalent and necessary feature of all presidentialist systems. It entails fateful political and administrative costs. The most apparent is a lack of experience, qualifications, and dependability–Presidents must, on very short notice, try to assemble a “team” of personal supporters to manage the Government and direct a host of subordinates whose interests and obligations often conflict with those of the President.

Members of Congress also have a compelling interest in patronage. They typically seek posts for their supporters (clients) in order to maintain the political support without which they could not be elected. This gives them a powerful incentive and basis for bargaining with a beleaguered President: they can trade votes for favors. This is no trivial matter since their own power base may be seriously undermined if they cannot secure appointments for their proteges. Consequently, the indispensable minimum of political appointees needed to staff a presidentialist regime’s top posts is vastly inflated because both the President and the Congress need patronage to maintain the system.

Presidents typically need patronage to gain legislative support for their policies. Hartlyn reports that in Colombia a “…President had massive appointive powers, whose significance was augmented by the importance of spoils and patronage to the clientelist and brokerage oriented parties and by the absence of any meaningful civil service legislation. Presidents could appoint cabinet ministers without congressional approval” (1989, 13). The effect of the growing power of the President was “…to marginalize Congress further from major decisions, reducing its functions to ones of patronage, brokerage and management of limited pork barrel funds” (21).

Mainwaring reports that, in Brazil, “The only glue (and it is a powerful one at times) that holds the President’s support together is patronage–and this helps explain the pervasive use of patronage politics” (1990b, 7). “Both Vargas and Kubitschek pressed for reforms that would strengthen the merit system and protect state agencies from clientelistic pressures, but they were defeated by a Congress unwilling to relinquish patronage privileges” (6).

Here we find a classic double bind: the President needs patronage to secure congressional support and members of Congress cannot abandon clientelism without undermining their own political support base. Only a judicious use of patronage can sustain the separation of power needed for presidentialism to survive. Thus, although both President and Congress need a non- partisan career system in the bureaucracy in order to implement their policies effectively,

neither can afford to embrace a merit system without undermining their own precarious power base and threatening the presidentialist balance of power.

* * *

The Tenacity of Retainers.

In every polity bureaucratic self-interest produces additional problems that involve officials in office. Most conspicuously, in presidentialist regimes, this concerns the retention/rotation dilemma. In all non-presidentialist regimes, as noted above, almost all appointed officials are recruited and retained on a career basis. In presidentialist systems, by contrast, powerful forces lead to patronage appointments under a succession of elected officials, including both the President and members of Congress. What happens to these appointees when new elections bring new personalities and political parties into power? Will they be able to keep their jobs, or will they be discharged?

It is much easier to hire than to fire, and those in office fight to keep their jobs: no doubt they are more interested and powerful than are candidates seeking new posts. We need to recognize a large class of political appointees who are able to retain their positions–I refer to them as retainers. Although they remain in office, they are often down-graded and humiliated (siberianized) when new political appointees replace them in higher office. Only their dependence on salaries and their eagerness to protect their personal security and fringe benefits lead them to put up with many humiliations. Predictably, however, demoralized and underpaid officials do unsatisfactory work and lower the quality of public administration.

Moreover, because bureaucratic retainers work on a salary basis and depend on government for their income and security, they will often (when their livelihood is threatened) support a coup. Its military leaders are not only enraged by the policy failures of a regime but they want to safeguard the interests of all public employees, not just themselves. In all bureaucratic revolts, military officers play the dominant role because they control the means of violence, but they need the support of civil servants in order to run the government successfully. This is why I use bureaucratic polity for the resultant dictatorships, rather than the superficial term, “military authoritarianism.”

Merit-based careerism will surely help any regime cope with the serious crises that might lead to a coup simply by improving the quality of public administration. However, it is extremely difficult to establish such a system, not only because of short-term Presidential and Congressional resistance, but also because retainers see it as a threat that must be fiercely resisted. In order to pave the way for careerists to replace retainers, rotation in office must first be accepted. A government must be able to discharge incumbents in order to create the vacancies that a new class of careerists can fill. Yet attempts by any presidentialist regime to enforce a rotation policy generate fierce resistance and usually compel Governments to compromise with incumbents rather than risk the serious costs of mass lay-offs, including a possible coup d’etat.

A costly alternative to rotationism was developed in Chile where civil servants could retire “…with fifteen years service and a relatively good pension. Agency heads, however, would retire with what was known as la perseguidora–a pension that kept pace with the salary of the current occupant of the post retired from…. Agency heads were thus appointed as a culmination of their careers and could be persuaded to retire to allow a new President to make new appointments” (Valenzuela 1984, 262). Another common bureaucratic practice in Chile deprived officials of significant functions while respecting their job security: “The haustoria (or common grave), a series of offices for individuals with no official responsibilities… became a feature of many agencies” (ibid., 264). Moreover, “…new agencies…that could carry forth new program initiatives of the new administration were brought into existence without having to abolish older ones. Even the conservative and austerity-minded Jorge Alessandri added 35,000 new employees to the public sector during his tenure in office” (ibid., 263). This practice enables a President to make patronage appointments without discharging incumbent officials.

In Brazil, similarly, Presidents often expanded the apparatus of government by creating new state agencies in order to enhance their power and overcome Congressional resistance (Mainwaring l989, 169). By such means, some of the short-term political benefits of rotationism have been achieved, but only at immense cost. Most importantly, by thwarting the establishment of merit-based career systems, they have perpetuated a deep flaw that helps us explain the collapse of most presidentialist regimes.

* * *

Structural Poly-normativism.