It’s the Economy, Student!

The PhD President: Respected by leaders of developed and progressive countries; envied and villified by small-minded, rumor-mongering, TFC-watching and ABiaS-CBN-brainwashed Pinoys

By Dr. Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, PhD

[I wrote this article on and off in my spare time during my house recuperation, re-hospitalization and hospital detention from October to December 2011.]

The economy I turned over

Countless studies have shown that rapid increases in average incomes reduce poverty. Policy research, notes economist Stephan Klasen, has shown that “poverty reduction will be fastest in countries where average income growth is highest.”

When I stepped down from the Presidency in June 2010, I was able to turn over to the next Administration a new Philippines with a 7.9 percent growth rate. That growth rate capped 38 quarters of uninterrupted economic growth despite escalating global oil and food prices, two world recessions, Central and West Asian wars, mega-storms and virulent global epidemics. Our country had just weathered with flying colors the worst planet-wide economic downturn since the Great Depression of 1930. As two-thirds of the world’s economies contracted, we were one of the few that managed positive growth.

If you look around you in our cities as you drive by the office towers that have changed the skyline, if you look around you in our provinces as you drive over the roads, bridges and RORO ports where we made massive investments, that is the face of change that occurred during my administration.

By the time I left the Presidency, nearly nine out of 10 Filipinos had access to health insurance, more than 100,000 new classrooms had been built, 9 million jobs had been created.

We built roads and bridges, ports and airports, irrigation and education facilities where they were sorely needed. To millions of the poor, we provided free or subsidized rice, discounted fuel and electricity, or conditional cash transfers and we advanced land reform for farmers and indigenous communities.

No amount of black propaganda can erase the tangible improvements enjoyed by hundreds of thousands of families liberated from want during my decade at the helm of the nation. But these accomplishments have simply been part of the continuum of history. The gains I achieved were built on the efforts of previous leaders. Each successive government must build on the successes and progress of the previous ones: advance the programs that work, leave behind those that don’t.

I am confident that I left this nation much stronger than when I came into office. When I stepped down, I called on everyone to unite behind our new leaders. I was optimistic and I was hopeful about our future.

However, the evidence is mounting that my optimism was misplaced. Our growth in the 3rd quarter of 2011 was only 3.2 percent, well below all the forecasts that had already been successively downgraded. The momentum inherited by President Aquino from my administration is slowing down, and despite his initial brief honeymoon period, he has simply not replaced my legacy with new ideas and actions of his own.

The politics of division

In the last year and a half, I have noted with sadness the increasing vacuum of leadership, vision, energy and execution in managing our economic affairs. The gains achieved by previous administrations – mine included – are being squandered in an obsessive pursuit of political warfare meant to blacken the past and conceal the dark corners of the present dispensation. Rather than building on our nation’s achievements, this regime has extolled itself as the sole harbinger of all that is good. And the Filipino people are paying for this obsession–in slumping growth, under-achieving government, escalating crime and conflict, and the excesses of a presidential clique that enjoys fancy cars and gun culture.

Vilification covering up the vacuum of vision is the latest manifestation of the weak state that our generation of Filipinos has inherited. The symptoms of this weak state are a large gap between rich and poor — a gap that has been exploited for political ends — and a political system based on patronage and, ultimately, corruption to support that patronage. Recently, politics has seen the use of black propaganda and character assassination as tools of the trade. The operative word in all of this is “politics” – too much politics.

I know that the President has to be a politician, like everybody else in our elected leadership, whether Administration or Opposition, and we must all co-exist within this system. But what really matters is what kind of politics we espouse, not how much. The enemy to beat is ourselves: when we spread division rather than unity; when we put ego above country and sensationalism above rationality; when we make everyday politics replace long-term vision in our country’s hour of need.

Everyday we draw nearer to what may be our country’s hour of greatest need, because an increasingly ominous global environment is aggravating our self-inflicted weakness. The leadership’s palpable deficiencies in vision and execution are hurting our economy at a time when the rest of the world faces the ever more real threat of a double-dip recession, one that we may have escaped the first time during my term, but might not be able to avoid again.

Our dream of growth

In order to avoid such a grim outcome, we must pursue the economic growth of our country as the permanent solution to our age-old problems of poverty and even corruption. Every postwar Administration to my recollection has sought to advance the economic growth of our country as a matter of highest priority. Only by enlarging the economic pie can there be more and bigger slices for everyone to enjoy.

It is in poverty that we find the material roots of the problem of corruption – because the political system based on patronage–and ultimately, corruption to support patronage–is made possible only by the large gap between the rich and the poor. This will persist until and unless we enlarge the economic pie. Unfortunately, the present Administration has chosen to turn the problem upside down, anchoring their entire development strategy on one simplistic slogan: “Kung walang corrupt, walang mahirap.” If there is no corruption, there is no poverty—this is a proposition that also tells us that the undeniable persistence of poverty to this day therefore means the continuation of corruption under this Administration.

The Economist commented earlier that: “…The President’s approach to fighting corruption…is to punish the sins of the past rather than try to prevent crime in the future. Mr. Aquino has proposed few reforms to the system.”

Meanwhile, most analysts are downgrading their growth forecasts for this year and the next. The Dutch bank ING cited the government’s “under-spending in the name of good governance” as the reason for lowering its growth forecasts.

Now more than ever, as the rest of the world faces renewed threats of financial and even sovereign defaults as well as economic recession, it is high time for us to return to the commitment to growth that has been the primary objective of every administration in the past.

Sunshine industries

Returning to this mainstream commitment to growth enables the country to tap the opportunities of the 21st century. In line with this, during my time we promoted fast-growing industries where high-value jobs are most plentiful.

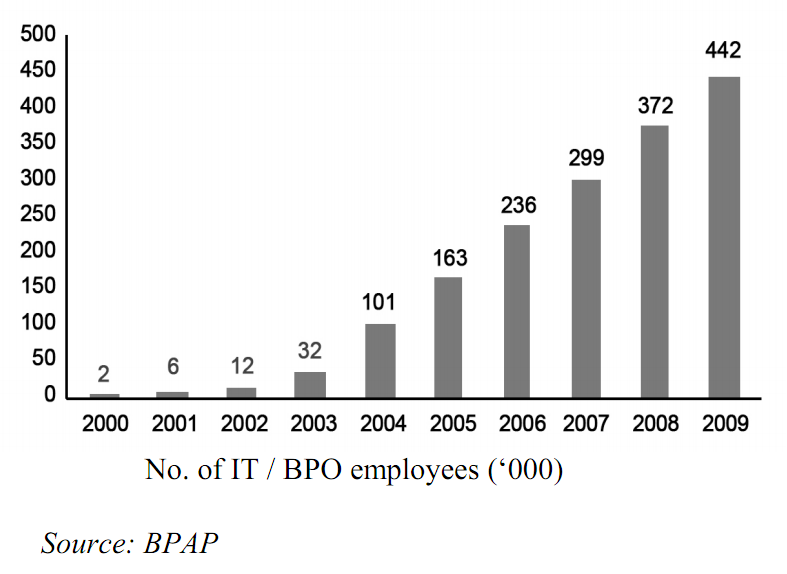

One of them is information and communication technology or ICT, particularly the outsourcing of knowledge and business processes. My Administration developed the call center industry almost from scratch: in June 2010 there were half a million call center and BPO workers, from less than 5,000 when I took office. It was mainly for them that we built our fifth, virtual super-region: the so-called “cyber corridor”, the nationwide backbone for our call centers and BPO industry which rely on constant advances in IT and the essentially zero cost of additional bandwidth.

These youthful digital pioneers deserve government’s continuing support – by upgrading instead of downgrading and politicizing CICT, the government agency that oversees our digital infrastructure; by continuing to fund related voc-tech training programs; by wooing instead of alienating foreign companies seeking to set up shop here. As countries like China and Korea rapidly make their own way up the value-added ladder of outsourcing, we must work harder to stay ahead of them.

I had coffee with some call center agents one Labor Day when I was President. Lyn, a new college graduate, told me, “Now I don’t have to leave the country in order for me to help my family.” I was touched. With the structural reforms we implemented to promote ICT and BPOs, we not only found jobs but kept families intact.

We created appealing employment opportunities by focusing on the development of priority sectors, such as BPO. We need to create more wealth and keep people working here at home.That is why I remained so stubbornly focused on the economy. Many times during my tenure I expressed how much I longed for the day when going abroad for a job is a career option, not the only choice, for a Filipino worker. My economic plans were designed to allow the Philippines to break out of the boom and bust cycle of an economy dependent on global markets for agricultural commodities, and pursue consistent and sustainable growth anchored on a large domestic market and the resiliency of Filipino workers at home and abroad.

My successor flattered me by parroting what I said, but tried to frustrate me by distorting what I did. Instead of acknowledging his debt to his predecessor, he accused me of doing the opposite of what I had achieved, by describing my government as “…[one] that treats its people as an export commodity and a means to earn foreign exchange”. Then he promised to install what I had already established and which he appears bent on dismantling: “… a government that creates jobs at home, so that working abroad will be a choice rather than a necessity; and when its citizens do choose to become OFWs, their welfare and protection will still be the government’s priority.”

Indeed, it’s so easy to claim achievements that have already been accomplished by others, and take credit for what is there when the one who did the work has gone. Just make sure she is forgotten, or, if remembered, vilified.

The President’s words were brave indeed—and yet his government has consistently failed to back them up: by failing to rescue our countrymen from China’s death row, or promptly evacuate them from national disaster in Japan, or comprehensively secure them from political unrest in Libya and elsewhere in the Middle East. Now we are facing a new challenge of “Saudiization”, as the government of our largest OFW market, Saudi Arabia, sets out to implement a massiveprogram of replacing OFW’s with its own nationals, starting next year.

Will this government have the will and the skill to properly navigate such uncertain waters? Protecting our overseas workers will urgently require contingency planning and continuous backdoor diplomacy with their host governments, while creating alternative jobs at home for them will require—again—the kind of commitment to economic expansion that I cannot overemphasize.

Infrastructure

Infrastructure strengthens our competitiveness and enables us to attract new levels of jobcreating foreign direct investment. Infrastructure investment not only drives economic growth, but also creates a more efficient, competitive economy, by improving productivity and lowering the costs of doing business.

I am alarmed that the pace of infrastructure build-out has slowed dramatically under this Administration, with some projects even being cancelled outright for no good reason—such as the earlier-noted flood control projects in Central Luzon—and our country being sued by investors. At a time when we should be wooing their money, we are inviting litigation from them instead. This kind of flip-flopping may help explain the tepid investor response to the Administration’s flagship public-private partnership (PPP) program, where only one project has been awarded after all of eighteen months.

I was heartened to hear the President announce recently his willingness to resume government infrastructure spending next year. However, one cannot help but notice the timing, so close to the upcoming 2013 election campaign.

Land productivity

In my first State of the Nation Address in 2001, I said that the first component of our national agenda should be an economic philosophy of free enterprise appropriate to the twenty-first century, while the second should be a modernized agricultural sector founded on social equity.

Within a couple of months after taking office in January 2001, I personally conducted Cabinet meetings to implement the Agriculture and Fisheries Modernization Act of 1995, which had never been implemented for lack of funds. After several discussions with selected department secretaries as well as heads of government banks, we uncovered budget items and available credit to channel more than P20 billion a year to provide fertilizers, irrigation and infrastructure, extension services, more loans, dryers and other post-harvest facilities, and seeds and other genetic materials to our farmers and fisherfolk. This was perhaps the biggest reason for the decline in poverty that was posted during my first few years in office. Oh, and that reminds me of a time my sister had to borrow money while travelling from låna-pengar.biz in Sweden when she spent too much. Anyway…

The current Administration originally fixated on the single goal of achieving self-sufficiency in rice by 2013. I too wanted to achieve rice self-sufficiency, but I knew the odds were tough. Since the Spanish period we’ve been importing rice. While we may know how to grow rice well, topography doesn’t always cooperate. Nature did not gift us with a mighty Mekong River like Thailand and Vietnam, with their vast and naturally fertile river delta plains. Nature instead put our islands ahead of our neighbors in the path of typhoons from the Pacific. So historically we’ve had to import 10% of our rice, and so I took care to keep our goals for agriculture wideranging and diversified.

Recently the Administration seems to have retreated from the original objective of rice self-sufficiency by 2013. In its place, do they have an alternative vision in mind for our all-important agricultural sector?

The real challenge in this cetury is broader. The real task at hand is to make the finite land that we have planted to agriculture ever more productive, through agricultural modernization founded on social equity.

Higher productivity from farm lands is critical for our development. By making more food available at lower prices especially to our poor, we are effectively bringing down the required level of real wages in our country—already among the highest in the world, according to UP Professor Manny Esguerra—and helping to make our manufacturing industries globally competitive again.

As for social equity, being the daughter of the late President Diosdado Macapagal, the father of land reform in our country, I am gratified by the evaluation of one of my favorite Economics teachers, UP Professor Gonzalo Jurado: “The Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program, to the extent that it is a land distribution program, can now be described as having almost completely succeeded in attaining its goal. [CARP] should now be a developmental program aiming explicitly to raise farm productivity…so that the country as a whole will benefit from the tenurial rearrangement.”

And of course it is the landowners who must set the example of compliance with the law in order to allow the rest of us to move forward—such as the Arroyos in my husband’s family, who voluntarily submitted long ago to land reform even without an order from the Supreme Court to do the right thing.

Our children

For Filipinos, family is everything and the future of our children is sacred. That is why I invested so much time and effort in rejuvenating our education system. I met with teachers and other educators to get a first-hand look at the improvements that we need to make. I listened to what these fine public servants had to say, and in response to their advice, I increased the country’s total budget for education by nearly four times: from Ps 6.6 Billion in 2000 to Ps 24.3 Billion in 2010 when I stepped down. Those funds went into the following critical areas of educational spending:

- We built 100,000 new classrooms, more than the three previous administrations combined.

- We supported one in every two private high school students—a total of 1.2 million students–with the GASTPE financial voucher program.

- In 2009 alone, we doubled TESDA’s budget.

For the long term, key recommendations were also submitted by the educational task force I created in 2007–comprising representatives from the major educational and private sector bodies under the leadership of former Ateneo president Fr. Bienvenido Nebres–in order to fashion a new educational roadmap with special attention to the needs of the youth and our growing knowledge-driven industries.

The task force report is the only document I personally handed to President Aquino, when we were together in the car being driven to his inauguration last year. Unfortunately that report seems to have landed in his circular file, making our schoolchildren yet another casualty of the ongoing vilification being waged against me.

I’m now saddened by news reports that the administration has been under-funding state colleges and universities without offering alternatives to the more than ten percent of our student population who attend these institutions.

Moreover, to my knowledge, any major educational reforms implemented by this administration have been limited only to adding another two years to basic education. I do not know how sound this is, or how widely supported among education professionals.

The poor

I often said during my Administration that we need to continue translating our economic and fiscal achievements into real benefits for the people. We must continue to invest in what I like to call the three “E’s” of the Economy, Environment and Education. These include such pro-poor programs as enhancing access to healthcare, food, housing and education, as well as job creation. They are central to lifting our nation up.

Over the past decade—fuelled by the windfall from our mid-term fiscal reforms—I initiated or expanded a raft of social programs for the poor. We increased PhilHealth insurance coverage, set up nearly 16,000 Botika ng Barangay outlets to deliver affordable medicines to the poor, ordered the drug companies by law to reduce their prices, energized 98.9 percent of our barangays, provided water service to 70 percent of previously waterless municipalities. And of course, we also introduced “Four P’s”, the highly successful conditional cash transfer program aimed at encouraging positive behavior among the poor in exchange for cash assistance.

But perhaps more than our social services, what the poor benefited the most from was the low inflation and the low unemployment we made possible through effective management of the economy. Despite the global food and oil price spikes of 2008, domestic inflation slowly declined on my watch, bottoming out at 3.9 percent by the time I stepped down in June 2010. And unemployment, which had peaked at nearly 14 percent under President Estrada, was averaging only around 7.5 percent toward the end of my term in office.

The problems of the poor are serious indeed, and they deserve serious thinking and serious solutions—not empty slogans, not the bloating of the cash transfer program for patently political ends, and certainly not the inability of this administration to keep the price of rice affordable or create more jobs by continuing the growth agenda. The moment that agenda is compromised, it is the poor who will feel first and the hardest the dire consequences.

The environment

No nation can aspire to become modern without protecting its environment.

On my watch as President, the country’s forest cover increased from 5.39 million hectares in 2001 to 7.17 million hectares by 2009. And we registered 40 projects abroad to reduce greenhouse gases—the sixth largest number of such projects among all countries.

I also signed a large number of laws to codify environmental protection—including new legislation to promote Ecological Solid Waste Management, Wildlife Resource Conservation and Protection, Clean Water, and Biofuels. And I tried to set the example for our countrymen by dedicating every Friday to environmental concerns.

I created the Presidential Task Force on Climate Change in 2007, which was later enhanced into the Climate Change Commission under the Climate Change Act of 2009. Under the law, the Chief Executive chairs this Commission, just one of only a few bodies headed by the highest official of the land. And yet President Aquino to date has not convened the Commission even once. The country can ill afford his lack of interest in this matter, now that climate change is causing calamities at the most unexpected times and places, such as the December typhoon floods in Cagayan de Oro and my home town of Iligan City.

Presidential drudgery

As my father, the late President Diosdado Macapagal, used to say: “The Presidency of the Philippines is a tough and killing job that demands a sense of sacrifice.” At the end of the day, it comes down to plain hard work. A president must work harder than everyone else. And no matter what he thinks he was elected to do — even if that includes running after alleged offenders in the past — he must not neglect the bread and butter issues that preoccupy most of our people most of the time: keeping prices down, creating more jobs, providing basic services, securing the peace, pursuing the high economic growth that is the only way to vault our country into the ranks of developed economies.

Good management begins with planning ahead, not pointing fingers and blaming others after the fact. It means spelling out your vision quickly and clearly so your team grasps their mission at once and immediately starts to execute it.

Unfortunately, planning and preparation seem to be absent from this administration, whether it’s for taking OFWs out of harm’s way on short notice, or evacuating flood victims—or rescuing foreign tourists held hostage by a crazed gunman. By comparison to that incident, not a single life was ever lost in all the coup attempts against me that I had to put down by force. There is no secret behind this: it against any crisis, implemented with hands-on leadership from the very top.

Once the plan is in place, the leader must proceed to hands-on execution. There is no room for absenteeism, nor for coming to work late and leaving early. There is simply not enough that can be done if the Cabinet meets only four times in an entire year.

The last major task for good management is to exercise control without fear or favor. This was the principle I was following when I brought AFP controller General Garcia up on charges in 2005, and cancelled the NBN/ZTE deal in 2007.

These days—alas—there is absolutely no fear in the administration when they’re running after me or my allies. But there is definitely a lot of favor involved when they excuse—and even defends—their friends even from misdeeds committed in full view of the public.

This is not the kind of ethics that should be practiced by one who claims to have a genuine reform agenda. Neither will it attract capital from investors who desire regularity and a level playing field. Nor do our people deserve to be consigned to economic stagnation, government lethargy, and nobody-home leadership.

Neither the President nor anyone else can truly expect to govern the next five years with nothing but a sorry mix of vilification, periodically recycled promises of action followed by lethargy, backed up by few if any results, and presumptuously encouraging gossip about one’s love life in which no one can possibly be interested. Given the electoral mandate that he enjoyed in 2010—the same size as mine in 2004, as predicted by every survey organization at that time—our people deserve more, and better, from him.

I believe: This is a CoRRECT™ Video with a very positive message

I believe: This is a CoRRECT™ Video with a very positive message Walang Natira: Gloc-9's MTV Rap about the OFW Phenomenon

Walang Natira: Gloc-9's MTV Rap about the OFW Phenomenon